Tsuwano, a Japanese village.

A little man wearing a gentle smile, shuffling through his morning, making tea for his neighbor, sweeping the porch, seeding the bird feeder. A pair of school-aged girls venturing out into their village with a few saved up coins, and a wealth of gumption. Authentic Meiji era homes with a few generations of families next to abandoned and vacated structures whose children took one-way trains to Tokyo long ago. Tsuwano is special.

The scale is the first thing you notice. Two-story homes with traditional Japanese tiled roofs, horizontal wood slatting, and sliding doors. The houses are pressed neatly together in rows organized by narrow roads. My first morning here was so quiet and calm I wondered if I'd found a village of about 5 people. Walking around orienting myself I found waterways on the side of the main road holding koi (colorful carp) fish. A small local

densha (train) rumbles through every hour or so and I hear the train signal as the barriers are slowly lowered. I wonder if you could get the whole village on one of these trains... probably not, but maybe if you tried hard.

Tsuwano is small, but somehow complete. The proportion, like the pace, is an invitation.

A Village of Surfaces

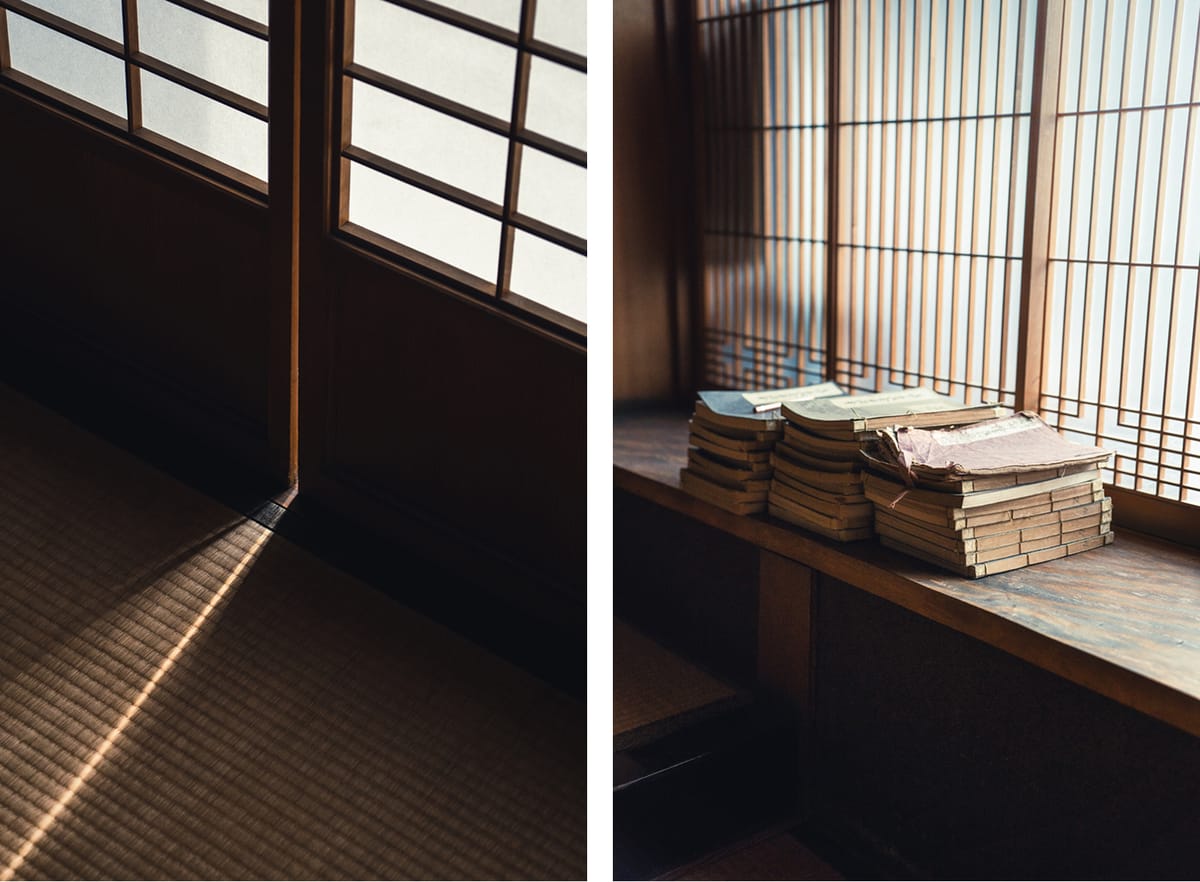

Entranced with the novelty of textures and their forms, I document them in shot after shot, collecting like a boy finding bugs in his backyard. Itabei plank siding in diagonal patterns. Modern corrugated metal painted to mimic woodgrain. Vertical kōshi lattices. Plaster expiring to show weathered cedar beneath. Rust blooming, time's signature on his artwork. Not blemishes, a vocabulary of form.

I learned much of this is the lineage of machiya craftsmanship from the 1800s to very early 1900s. Slatted kōshi-do doors to let light breathe, hand-carved ranma panels above entrances, kawara roof tiles crowned with decorative onigawara. Decay is understood, it's allowed, it's patina. The philosophical soil that grew this culture understands and embraces impermanence. Moss softens stone, wood fades in gradients under sun and weather. I'm curious if it's these patterns that make a kind of nest of calm that I'm able to rest in when I'm here.

I imagine that most locals probably walk past all this without seeing it, as I also do at home. These surfaces are of fingerprint of Tsuwano—and Japan. I have an idea of making a small book, one of two, of the textures of Tsuwano. I plan to send one to my new friends there, and one I'll keep for me.

Hospitality

The people in Tsuwano are textured as well. At Fukuzushi, a family sushi shop, the son in his fifties worked beside his father. He asked about my Japanese, smiled when I stumbled, as he did with his English, but we both encouraged each other with appreciation. Iie, iie, jozu jozu! (no no, it's good!)

At a soba shop, a grandmother greeted me like I’d wandered into her living room. After a delicious meal I also requested quite a generous helping of chestnut snacks, kuri yōkan (seaweed agar, sugar, with chestnut pieces). She checked my order several times, making sure I knew what I was spending in yen. I left full of soba, and her gentleness. She apologized constantly with bows and sumimasen for nothing in particular. It actually gave me more understanding of my wife, Ako, and how I tell her not to apologize so much! In Tsuwano I think I finally understood it. Apology here is less about fault and more about smoothing the edges of connection.

Listening wide open

My favorite hours were spent learning. A calligraphy class with a tiny little master calligrapher with the heart of a bear. Gruff, but kind, she taught me to write kumo (cloud). A tea workshop at Komien Tea House, where Adrien guided me through blends of sencha, hōjicha, zaracha, ginger, and yuzu—all grown and roasted locally.

Komien is a family business, started 130 years ago. Now inherited by Rumi and shared with her French husband Adrien. These two linger in my mind weeks after leaving Tsuwano. Warmth, craft, presence. I stayed in the little guest house above their business. Their story, French and Japanese, raising their daughter in this slow village. It feels like a metaphor for Tsuwano: old and new, rooted and open.

Lingering

Some places you pass through. Some places imprint. There's a scale in Tsuwano that makes human connection inevitable, and a pace that allows for it to open as it will, on its own. Being an outsider sharpens the details; the sound of crickets speaking Japanese, the smell of woodsmoke, the feel of moss hugging the wall.

I’ve told Ako that we're coming back. Tsuwano is where work and reflection sit together for tea. A place to write from, or to remember what your hands can still make. That's my souvenir; to return.

More photos from the journey will keep showing up here.